Somewhere

on the long bus ride back across the country, Meneeley woke up with numbness in

his arm. Don’t panic, he thought, as scenes of hospital gurneys sprang to

mind. Sit straight and let the blood

bring back life…

To memory,

the adventures the young Navy medic found along the road could be summed up to a

single surreal night walking the Las Vegas

No longer a

boy, the medic was going home. Near

No longer a

boy, the medic was going home. Near

When his bus finally pulled into Wilkes-Barre

In the last

shuffle of Meneeley’s discharge, communication with his family had become

difficult. During this period, his grandfather passed away.

Uncle Paul,

newly married, received the Halter home as a wedding present. By proxy, Ed’s father absorbed his son's portion of what

would have been his mother’s inheritance and upgraded the family house. After

hugs and welcome home’s all around, Edward was shown around the new home, pleased

to discover the property had a little shed out back he could later convert to a

studio.

The novelty

of the son returned-from-war was exhilarating, but as the energy of reunion

began to fade, tension with his step-mother seeped in to fill its place. Once Meneeley exhausted his neighborhood rounds

reconnecting with old friends and collecting the parcels shipped back from California

“My step-mother saw me

as a considerable threat,” Meneeley recalls. “There was no denying it.”

Carpentry

came easily to junior as Ed and his father worked on fixing up the new family home. Once the

house was up to par, Ed began fixing up the small shed in the

yard, his relationship with his

step-mother still workable as he unwrapped his parcels of brushes, oils and

rolled canvases sent ahead from Riverside

In terms of

colleges, there was the safe, easy choice: Kutztown Teacher’s College, a well-regarded

rural university and after 30 years teaching, retirement. Marriage. Children. White picket fence.

|

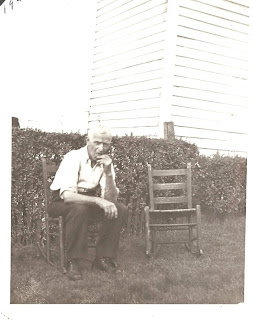

| Ed's first studio, photo taken in 2010 |

"I cared about Gloria and Beverly," he recalls, "But I eventually had to blow the whistle. The next day I shouted at my parents about running a

whorehouse!”

Intent on a second escape, Ed listened with delight to a radio advertisement of an

experimental school opening in Wilkes-Barre, T Greenwich

Village .

3

Enrolling

in the Murray School ,

Ed began feeling comfortable and productive for the first time since departing

his last patients in California

Gloria,

please tell Edward not to wear his filthy shoes in this house, she command

her daughter through clenched teeth.

But before his step-sister could

grunt a protest, Ed fired back, dear

sister, please tell your mother that if it weren’t for the nude model waiting in my life drawing class I

would be obliged to shove my foot in a place where the sun refuses to shine.

It went on like this for weeks

before Meneeley finally found the courage to confront his father. Finding him

largely unsupportive, Edward began renting an old grocery store front on Madison

Street Wilkes-Barre

During performances, Meneeley

inevitably went along to listen and dance. At the hometown shows he often

encountered Viola, Dave’s younger girlfriend whom Ed first met after basic

training before shipping out West.

Together they would drive to see concerts, motoring to Philadelphia

Back in Wilkes-Barre

At the Murray

School

“I don’t

know which one of you fuckers did this but that’s the last time I work in this fucking

space!” he yelled, before returning with his signature smirk. “But

you’re still going to see me everyday.”

4

As classes

progressed, students responsible for their own materials felt the pinch. For Meneeley, money was tight. Aside from paints and canvases, heating coal was

expensive, so he began ordering it and charging it to his family to stay warm. Record sales were weak and private lessons, more of a summer activity, dried up in winter. Worst of all, his GI Bill was running

out.

Luckily for Edward, the founder

of the school, Alexander Murray, began showing an interest in him. Despite Ed's brash methods, the prevailing

attitude of the faculty expressed a confidence that Meneeley might actually become an

artist, a concept Edward didn’t quite understand.

Alexander

Murray, brother of Senator Murray from Montana , did his

best to recruit artists from the Arts Students League in New

York Wilkes-Barre

and Scranton Murray later invited Meneeley to

accompany him on buying trips to New York

On his first night in the city at the

On his first night in the city at the St.

Moritz

On his first night in the city at the

On his first night in the city at the

Many other

aspects of New York caught his attention, like a lesbian

bar in Greenwich Village adorned all in red velvet he

mistakenly stumbled into where he couldn’t tell who was male or

female.

His first

trip to MoMA, Ed walked right past Guernica

At first Mondrian and Malevitch enrage

him. Later they become major influences.

“A white

canvas with a white square floating in it...at first I thought, Oh God, fuck

it, that’s not art! I was angry. There was nothing there. Just a funny little

square on a rectangle. Why should I care

about it?”

|

| Kazimir Malevich 'Supremetist Composition White on White' MoMA 1917 |

“Later, I thought, why am I still thinking about it? Why can’t I get it out of my mind? Because it was a crackerjack work of composition! As I began

to read and learn more, I slowly realized I was being influenced. It was about culture. After a lot of thought,

I realized the square wasn’t on the

canvas but was rather with the

canvas. It turns on the entire rectangle and totally energizes the canvas. A

person seeing this can’t eat pieces of it, but rather, is forced to swallow the

whole thing.

“Suddenly I

woke to the fact that art was not about making paintings, it was about revealing

some kind of cultural energy. Each

time—30s, 40s, 50s, etc.—has its own energy. Art was slowly changing the view

of humanity. And I certainly was no longer as idealistic as I once was.”

5

After three years at the

“I felt

terrific about the piece,” Ed recalled. “What impact it had on my family, I

have no idea. Certainly, though, in the community, it took me from being an

anonymous student to becoming a known entity.”

Locally,

Meneeley discovered a large Jewish population in Wilkes-Barre

Slowly, he

began selling some work and patrons invited him into their homes. Just

like his first stunt in the military, Meneeley couldn’t believe the food. He

began to appreciate Jewish people because they seemed to care about culture

whether through financing the orchestra or reserving a row of seats in the theatre.

Just as momentum built in his life as an artist, he received papers recalling him for the

Korean War. Full of dates about reentry

and exams written in legalese, Ed didn’t pay much attention to them. He was too

busy cavorting with an older woman, a jazz buff, who spent her money lavishly on him with trips into the city for a weekend. They

ate well and stayed in nice hotels, witnessed Dizzy Gillespie perform at

Birdland, followed by the German play “Enemy of the People” the next.

At the end

of the play, people stood up and applauded. Meneeley stood with them, caught up

in the enthusiasm, but he still wasn’t quite sure what it all meant.

|

| Anita Oday |

One Monday

morning, Meneeley reported to take his Navy exams under the impression he still

had 30 days to straighten up his affairs, but he had misread the summons. Once he arrived he couldn’t go back.

Panicked,

he found a telephone and was forced to plea with the operator for a connection

home so he could have his friends take care of closing the

store. In just a few minutes he would enter the next building and thrust officially into war.

6

“Welcome

Aboard.”

From New

York , Meneeley was quickly transferred to the Navy Yard in South

Philadelphia where the master-at-arms sent him to get outfitted

and report the next morning to ambulance duty. His first job was to pick up a

Vet suspected with pneumonia. Meneeley was given keys to the medicine cabinet,

but after picking up the patient, he didn't recognize

any of the drugs. He hadn't had

the time to be brought up to speed, so he shouted for the driver to turn up the heat and

get back as quickly as possible.

Back at the

hospital, Meneeley blew his top.

"How was I

supposed to know penicillin was given up for ampicillin? I was never given

instructions on dosages…these are human

beings!”

His

insubordination was tolerated, he recalls, mostly because medics outnumbered

regular military. Medical needed to be

fast and efficient. “Fuck saluting or wearing all of your uniform, it didn’t

matter once you got the job done,” Meneeley recalled. “After that I took a walk to cool off, then

decided to try to understand what type of beast I was now a part of, so I went

into the hospital elevator and got off at every floor to see what was going on.”

Orthopedics.

Easels?

“You’ve got

artists here?” he asked.

"Yes,” Chief

Petty Officer responded.

“Need

another one?”

“No.”

Defeated,

Meneeley turned to go.

“Know

anything about photography?” the CPO asked.

Meneeley’s

quick pivot and outstretched arm caught the door before it sealed in front of him.

Off to the

right was a photography studio, with much of the same equipment as his grandfather’s

darkroom—his uncle’s camera, chemicals, fixers, trays, rolls of film.

“We need somebody who can make prints.”

Meneeley

took a breath.

“Do you know

what this is?”

“A

negative,” Meneeley responded.

“Well then

go on. There’s the darkroom. Make me a print.”

Inside the slick

curtained doors, the world was totally blacked out but for the red light and

the sting of chemical odors. On a table

rested a motorized system above trays to facilitate the process.

“It even

rocked itself!” Meneeley exclaimed.

The print

still wet in the tray, he showed the officer, who immediately picked up the

phone and had him transferred.

A career in

photography had begun.

7

After

earning the respect of his colleagues, Meneeley’s duties began to expand and

eventually he would work on the in-house newspaper circulated throughout the hospital.

Obsessed with his new toys, he began practically living in his photo studio,

teaching himself to master the equipment, eventually developing an efficient

system for developing and recording prints.

Another aspect

of his job involved taking photos at officers’

parties. On his first assignment, Ed

forgot his flash, so he never loaded any film and pretended. As the night wore

on, Meneeley began paying attention to a particular officer eagerly intent on a

much younger woman. Suspicious of having

been documented with a woman other than his wife, the officer responded angrily

and insisted the film be ruined.

Overall the

majority of medics were from WWII. Relaxed veterans, some refused to wear Navy

clothes or salute. “We did the job,” Ed

recalled, “but we didn’t always adhere to Navy protocol.”

Most

photography assignment consisted of documenting dead people from surgery. Specimens were shot in Koda-Chrome. During

these depressing months, Meneeley and others spoke of how they’d been suckered

back into a war in which they only witnessed the death and diseased.

“Everybody who

had taken advantage of Federal money was brought back into it. There was no draft. For the doctors and

full-time nurses a medical education was expensive, so there was a seemingly unlimited

amount of money for photography.”

Before a wall

painted with a black measurement grid, Meneeley snapped pictures

of naked patients displaying infections, many frostbitten with gangrene,

as research materials. Later

documentation would provide the answer to questions like Does the

body slink lower after surgery, etc.? The ships coming home were full of educational

material, most awaiting amputations and already addicted to morphine, delivered from Korea

Meneeley

expressed the public’s limited awareness of the war. “Soldiers came back and no one seemed to know

what they were talking about. That is

why it was so hard for them. It wasn’t an official war so banks could foreclose

on the homes of Doctors who had been shipped overseas at drastically reduced

wages. They would come home to wives put out on the street and many couldn’t

handle the pressure. Because the war was more of a police action, the same

types of protection weren’t there for them.”

One of the

most interesting assignments for Meneeley was to photograph a patient’s who had

died aside a steam pipe after wandering off and getting lost in the bowels of

the hospital. Arriving to witness a body

blown open and skin peeling off, Meneeley described the corpse like a

person wrapped in lace, with remnants of his skin hanging delicately on the surrounding

pipes.

“It was

like Mrs. Habersham, living full of decadence with a dining room table covered

in moss. Table is always set. Rats running around. She hires a little boy to

play with her niece, and later tells him she’ll break his heart when done. It

was that kind of atmosphere.”

Every now and then, while sipping coffee on his floor’s common area, a body would fall past the window.

Suicides.

In this

depressing environment, Ed recalls the prevailing attitude as “Why

respect the establishment when the establishment didn’t respect you?”

That in

mind, he began to hoard supplies

with the intention to create art.

.

8

After his

first year, Meneeley was transferred to a civilian hospital outside the base

where most military operations took place.

Being the headquarters of the district, they had their own illustration

team responsible for propaganda posters and other graphic materials.

Ed was one

of few enlisted men in this new hospital. The rest were psychologists,

scientists, chemists, physicists, etc. Since they had no photography department, Meneeley felt his move was due to his perceived work ethic, though most of the time he was creating his own experimental photographs unbeknownst to the others.

His first

assignment: create a poster to elicit concern about the amount of food being

wasted. It would be put on every sub,

ship, etc. Meneeley was told they had gone through a lot of trouble to get him

and they hoped he would be part of the team.

|

The

equivalent of the art director thought it was terrific, but many who saw it

over the course of a weekend complained.

Monday morning, a group of Meneeley’s superiors recanted. “This has been

successful and is very moving, but it’s upsetting to people. It offended

the cooks. But we still want to use it.

Can you just change some of the images and put some lettering on it?”

“You can do

whatever you want with it,” he responded, “but I won’t touch it.”

They were

confused. “Why can’t you just…?”

Ignoring

their pleas, Ed started on another poster.

His

superiors fumed.

When he

left to use the bathroom, a group cornered him. “Why are you being a radical

son of a bitch?”

“Look, I

didn’t ask to be here. All you have to do is transfer me back.”

Forty-eight

hours later he was back at his old position on the contingent he would still

perform their assignments part-time.

9

Back to working

before/after surgery shots on a tripod, Meneeley photographed hundreds of naked gangrene amputations.

“Somewhere

along the line a mistake had been made. Someone thought of Korea

In some

instances, Ed photographed during surgery. One stinging memory dealt with a

person having their face peeled off to remove cancer from their lip. Surgeons

took the jawbone out, wired it temporarily while casting a piece of the removed

jaw.

“It’s

pretty amazing to see a person’s personality removed like that!”

Meneeley

continued the surreal work of morgue research photographer. Assignments had him shoot close-ups to be later used as educational materials. He remembered

the sound of cut ribs resembling a xylophone.

Beneath the skin and bones, he recalled, “colors are amazing, particularly

the organs of smokers which made the colors enhanced.”

At the same

time, Meneeley was gaining experience with the best equipment and technology

available. Ecktokrome took a long time to develop, yet it was possible to get the

processing performed locally. Kodachrome

remained under control of Eastman Kodak, and had to all be sent Rochester ,

New York

The experimental

equipment lab still kept him on as a consultant. The rest of the workers, mostly civilians,

left after their 9-5, so many weekends and evenings he had the place to himself

and all its equipment and materials. During this time, he began producing

sculptures out of Plexiglas cubes, and later, linear constructions made of

welded Pyrex tubing, which would be the subject of is first solo show on Rittenhouse

Square.

As his time

during the Korean War Recall wound down, he set out on a mine-sweeper mission

around Cape May . There,

erosion had washed in an entire street. Watching from the deck, it was the

culminating moment compounding the surrealistic experiences of the past few

years.

“Today, advertising

has blown the back end off of surrealism! At the time it looked to me as though

Pompeii

During his free

time, Meneeley took to painting from the hospital roof. Looking north, he could

see all the quasi-huts filled with morphine addicts.

“From my

vantage point, it was easy to visualize the amount of morphine addicts about to

be dumped on American society. The market was right in front of me.”

Anticipating

his discharge, Meneeley began mailing photographic equipment to friends on the

outside to keep it safe until he arrived.

10

Finally

discharged, Meneeley remained in Philadelphia

In 1952, Ed

showed the Pyrex sculptures as his first solo exhibition at the Donovan Gallery on Rittenhause

Square University

of Pennsylvania

Opening

night is a disaster.

A terrible

snow blanketed the guests’ heavy coats. Many, mistaking the sculptures for coat

racks; threw their damp, heavy wools over the transparent sculptures. Two-thirds

of the show was destroyed, including one huge piece Meneeley had just carried

across town.

His second two

shows at Donovan consisted of wooden structures and

paintings. Meneeley recalled the work “unlike the spare, linear style of the

sculptures. The paintings used a heavy palette knife technique, exploiting the

subservient texture and color of the material, determinedly expressionist and

gestural – reminiscent in the quieter works of Tobey, and in more communicative

ones of Frankenthaler and DeKooning.”

Later

accounts recall it was a loosening up in his character as he began to find his

way both artistically and personally.

At about the same time, Ed learned his old anatomy instructor at the Murray

School , John Cabor, was now working at the School

of Visual Art on 23rd

Street Manhattan

Soon after

his third show at Donovan, the gallery closed. Recognizing more opportunities

existed in New York, Meneeley plotted a course to take advantage of his

second installment of the GI Bill.

During his first

few visits he witnessed how Abstract Expressionism began exploding onto

the scene, receiving both critical and popular attention. Seemingly divided into two schools, Action Painting and Color Field, this new

breed of painter sought to take in worldly impulses, confront them with the

powers of the unconscious, and leave the imprint of raw emotion on the bare

canvas. Paintings that dove below the surface

details of the world. The aftermath of legendary battles of spirit.

Where is the next part of this? I'd like it for my grandson. Viola

ReplyDelete