|

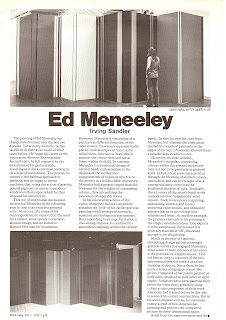

| Ed Meneeley |

When I first met the artist, I wasn’t sure if I could take him seriously.

In an age before google, his stories about befriending the likes of Franz Kline, Frank O’Hara, and Lee Krasner while also influencing Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol seemed far-fetched. I was equally skeptical of his resume boasting

The Tate London, The Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a long list of solo and group exhibitions in the United States, England, Ireland, and Greece.

Meneeley was an artist, of that I was sure. The massive abstract and color field paintings in his studio were proof enough. Pounding his fist on the table, he would go on for hours about “the essential role of culture” before spinning off with a giggle about knock-off sculptures hidden under the floorboards on the Greek Island of Lefkada, the humbling sensation of standing before ancient cave drawings, or how to properly steam an artichoke.

Intrigued, I listened.

About the time I was finishing my undergraduate degree, Ed asked me to write an introduction for the catalog of the drawings. Unbeknownst to me, my short essay attracted the attention of Wayne Adams, a longtime Meneeley friend/collaborator.

|

| Douglas Albert, Ed Meneeley & Wayne Adams |

Years passed and I moved away. One morning I received a call. I had never spoken to Wayne before, but our mutual friend was in trouble. In his early 80s, Ed suffered a mild stroke. A documentary film crew from London, where Meneeley lectured at the Central School of Art, had just finished filming an interview with him about the trans-Atlantic art scene in the 1960s onward. Wayne and I wondered, where was the recognition on this side of the Atlantic? With a renewed sense of urgency, we hatched a plan.

|

| Sainte Chapelle, Paris |

I always enjoyed Ed's tales about his time as a Navy medic during WWII when Marlon Brando lived on his ward in Riverside California while filming his first feature role in

The Men. Or about how Ed and Franz Kline hit if off after meeting at the Cedar Tavern in New York, calling out Native American place names like Tamaqua or Mauch Chunk as though they spoke a secret language after discovering they had common roots in Wilkes-Barre, PA. Another of his favorites was brunch with Lee Krasner the morning after his Electro-Static Prints were reviewed in the New York Times, how a bottle of Vouvray helped get his car out of a ditch, and how his life forever changed as he bathed in color at Sainte Chapelle.

By the end of the night, I often thought: is he for real?

Now I had my chance to find out if the old man was telling the truth. After five years sorting through massive boxes of papers and flying around the world to interview his friends, family and former students; I am left with a simple truth: too often the venerable among us have hugely inspiring stories to tell if only we would be patient enough to listen.

What follows is Ed's story, the culmination of a drunken promise made nearly a decade ago. How, from his own mouth, he ended up alone and penniless, nearly forgotten about after a rich lifetime of love and adventure...all the while producing magnificent works of art.