We felt the moral crisis of the world that was a

battlefield,

a world that was being laid to waste by the massive destruction

of

a raging world war…it was impossible to keep painting like before –

flowers,

reclining nudes, or musicians playing the cello.

Barnett Newman

On December 7th 1941 ,

Japanese pilots bombed the Pearl Harbor Naval base on island

of Oahu United

States

Months

later, Edward Hopper painted Nighthawks,

an iconic depiction of loneliness, and Peggy Guggenheim opened Art of this Century at 30

West 57th Street Manhattan

As the

world shifted under Hitler’s Germany Wilkes-Barre ,

Pennsylvania

"We interrupt this regularly scheduled program with news that the Japanese have invaded Pearl Harbor..."

Edward, who had for weeks had been contemplating a recruiter’s promise of money for college on the GI Bill, stood up and announced, “I’ll be in that!”

"We interrupt this regularly scheduled program with news that the Japanese have invaded Pearl Harbor..."

Edward, who had for weeks had been contemplating a recruiter’s promise of money for college on the GI Bill, stood up and announced, “I’ll be in that!”

Fueled on beer and whiskey, the family found room to chuckle at the youngster’s readiness

to go to war.

"It’ll be

over before you are old enough to go,” his uncle replied, rewarding his nephew’s

courage with a pat on the shoulder.

But he would show 'em.

Weeks later, Edward marched over to the rail station where his father worked, and with his most courageous stage voice, said, “I feel as it is my duty to represent the Meneeley family in the armed services during a time of war.”

Weeks later, Edward marched over to the rail station where his father worked, and with his most courageous stage voice, said, “I feel as it is my duty to represent the Meneeley family in the armed services during a time of war.”

|

| Meneeley Jr. |

Soon taking the steam train to Harvey’s Lake to swim away the summer or kite-sail over the winter ice would be just a memory…dancing until

collapsing into a hysterical pile with Beverly, his double social life, the

scourge of his step-mother. Warm, lazy

Sundays on New Grant Street with his uncles and grandfather.

Hopeful farewells gave way to tears as Edward Sterling Meneeley Jr.

and Hallister Hogan boarded a train for Samson ,

NY

But the

entertainment of the young seaman was brief.

Meneeley’s short flirtation with civilian life ended with boarding another

train, this one to California, stamped

non-priority cargo. There were times when the train sat switched-off for

hours while more important materials sped past. The sun’s fierce breathe

grew hotter and drier until the passengers began to ration water.

But the

entertainment of the young seaman was brief.

Meneeley’s short flirtation with civilian life ended with boarding another

train, this one to California, stamped

non-priority cargo. There were times when the train sat switched-off for

hours while more important materials sped past. The sun’s fierce breathe

grew hotter and drier until the passengers began to ration water.

It wasn’t long before the reigning masculine hierarchy became known.

“Hola Pecker Checker!”

One afternoon, while standing in the doorway to the closet where all the used casts were thrown, Ed stared transfixed. The tangle of white limbs waiting on a

pile to be thrown away struck him with the same emotion he would

later feel while looking at George Segal’s human-shaped sculptures in white

plaster.

As the weaponry of warfare became more sophisticated, so increased the number of complex spinal injuries, all of whom needed four meals a day and constant physiotherapy. Perhaps partly due to the extravagance of the commandeered setting, a large number of hands were available at all times and patients were well looked after.

Although highly unusual, at Riverside

His first morning after, hung-over and dying of thirst (only to drink some water and feel like he was drunk all over again), Ed woke up to the prodding of the same group of nurses he had spent the night partying hours before now full of pep and happily going about their morning routines as usual.

Stealing

him immediately away to the linen closet, the nurse shook him by the shoulders,

“Look, you have to go back there and finish up!

There’s no one else.”

Due to Riverside's proximity to

Due to Riverside's proximity to Hollywood

Long after

the Japanese surrendered, Meneeley and other medics remained working to strengthen

their patients, hoping to build them up in order to go home. Slowly, wives, mothers and sisters worked

their way to California

The Navy’s lease on the country club was winding down and patients trickled slowly back to civilian life.

The hospital

finally closed and the grounds refitted to a

place of private escape for privileged citizens of suburban Los

Angeles L.A.

2

Boot camp began

with the usual physical rigors. Running,

push-ups, discipline. The shaping of the

soldier. But what was most incredible to

Meneeley was the food.

While most recruits

botched at the mess hall, Hal and Ed approached the chow line with dropped

jaws. They had never seen so much

food. Equal amazement came with the

realization they could eat all they wanted, just as long as they cleaned their

trays.

One of the few boys in the shower without pubic hair, he was referred to as “the chicken.” After a medical

examination, Meneeley was diagnosed with malnutrition and received corrective surgery to

remove teeth abscesses. Deep within a morphine stupor, Ed

envisioned his step-mother hosting Eastern Star meetings wearing jeweled

tiaras while hushing the kids onto the back porch with the same plain old tomato

sandwiches.

His body

replenished and back on track, Meneeley displayed an aptitude as a marksman and

was put in charge of a dozen rifle ranges. In this position, his bossiness thrived under

the auspices of others’ ineptness to hit the targets. Ironically, the less proficient trigger fingers only created more work for him repairing the blasted sand piles.

Throughout

training, Hal and Ed bunked together and shared work details. The pair made a pact back home in Wilkes-Barre

3

While on

leave, Meneeley’s two-timing friend Dave introduced him to his pair of young

ladies. While Viola was technically Dave's “girlfriend,” he was seeing another more libidinous young lady on the sly. Taking it upon himself to entertain whichever

young lady was free at the given moment, Ed’s dual short flings helped fill

in the gaps missing from his experiences with his stepsister.

But the

entertainment of the young seaman was brief.

Meneeley’s short flirtation with civilian life ended with boarding another

train, this one to California, stamped

non-priority cargo. There were times when the train sat switched-off for

hours while more important materials sped past. The sun’s fierce breathe

grew hotter and drier until the passengers began to ration water.

But the

entertainment of the young seaman was brief.

Meneeley’s short flirtation with civilian life ended with boarding another

train, this one to California, stamped

non-priority cargo. There were times when the train sat switched-off for

hours while more important materials sped past. The sun’s fierce breathe

grew hotter and drier until the passengers began to ration water.

Sometimes, when stopped for long periods, local women approached from the horizon of flat farmland

with baskets full of sandwiches and sodas.

Ed remembers reaching out the window to receive the offerings, but never

being allowed to disembark. The women seemed accustomed to the idea, knowing

the trains would be there, perhaps en route to reinforce their own family

members stationed far away from home.

“There was

a sense of people taking care of their troops,” Meneeley recalled, “Though at

that time I wasn’t fully cognizant I was a troop until medical training began

and broken soldiers appeared.”

In a time

before air-conditioning, the dry heat of the cross-country trek invited most of

the men to air out their shirts, which often made it difficult to discern

commanding officers. One particular night,

Meneeley was assigned car duty and remembered being forced to grapple with an

un-uniformed officer for not saluting.

“You aren’t very attentive,” the officer scolded him, reversing his choke

hold. “People could sneak up on you and stab you in the back!”

“You aren’t very attentive,” the officer scolded him, reversing his choke

hold. “People could sneak up on you and stab you in the back!”

“You aren’t very attentive,” the officer scolded him, reversing his choke

hold. “People could sneak up on you and stab you in the back!”

“You aren’t very attentive,” the officer scolded him, reversing his choke

hold. “People could sneak up on you and stab you in the back!”

Sufficient “uncles” yelped and gasping for breath, a strange sensation came

with a troubling realization that the officer was a Marine.

Upon

arrival in San Diego Balboa

Park

As his name was read, he administered his first inoculation to the person beside him, plucking his skin in a ceremony of sterilized water. A few fainted and fell out of line.

As his name was read, he administered his first inoculation to the person beside him, plucking his skin in a ceremony of sterilized water. A few fainted and fell out of line.

Soon after

the onset of active duty, an ominous realization set in: Navy medics shipped

out with Marines.

4

Prior to

1942, Southern California ’s Rancho Santa Margarita y Los Flores was a rough and ramble 123,000

acres of pristine, potential energy. War

fervor an undeniable impetus, today it is one of the largest U.S. Marine Corps training

grounds in the country, Camp Pendleton

It wasn’t long before the reigning masculine hierarchy became known.

“Hola Pecker Checker!”

Marines commonly derided

their Navy counterparts, especially outside the hospital and after driving two

hours into town for a few drinks. Interspersed

with mischievous laughter, Meneeley recollects:

To the Marines, we were all sissies…until

they had some type of medical problem.

Then they couldn’t do enough for you—buy you beer, act as

bodyguards. One somehow got the use of a

convertible, so we picked up some girls, driving to a hillside where it was

like Lovers’ Lane. It was my first

encounter with a rubberized girl. She

acted like she wanted to put out, but she wore a girdle and none of us could

figure out how to get the damn things off. Later we’d get back to base and still

be horny. And without air-conditioning, everybody

slept buck-naked. You can imagine what

kind of scene the combination of those factors late at night played in the

overall tinderbox of what was going on sexually at that time….

5

Meneeley’s first

assignment was the tuberculosis ward and required a tedious routine. Prior to his shift, he changed clothes in the

vestibule, putting on a clean smock, mask and gloves

before performing his rounds. Once

complete, he took everything off, showered and put back on his regular uniform. Periodically he was tested to make sure

nothing got into his system.

To clear his head, on weekends Ed and others took liberty in Tijuana where muchas chicas bonitas danced

and servicemen drank tequila into a state of hyper-sobriety.

Surviving

his stint with TB patients, Meneeley’s request for transfer was eventually

approved. Orthopedics was an entirely

different animal, one often met screaming in pain with the onset of broken

limbs. Nonetheless, at least his patients now had

room for rehabilitation and the opportunity existed to forge more hopeful connections

with other human beings.

|

| George Segal 'Holocaust' |

“In those days," Meneeley said, "They had just come out with pre-moistened plaster bandages, so you didn’t have

to go through the trouble of taking

gauze and making plaster and mixing it together and putting it on. In that closet, as in Segal’s work, I

witnessed the broken’s desperate longing for life.”

Despite these

new awakenings, Ed jumped at the opportunity to escape when he noticed a bulletin seeking volunteers

to work with paraplegics coming back from the war.

6

The

barracks in Riverside Hollywood glamour in a beautiful

hillside resort. Effectively a country

club leased to the Navy as a temporary hospital for paraplegic patients,

Meneeley’s new station was an all-go situation in which the surgeons, nurses

and staff had to be available for around the clock care.

As the weaponry of warfare became more sophisticated, so increased the number of complex spinal injuries, all of whom needed four meals a day and constant physiotherapy. Perhaps partly due to the extravagance of the commandeered setting, a large number of hands were available at all times and patients were well looked after.

As a small

indulgence, Meneeley sneaked a suitcase record player into the

barracks. During night duty, he often listened to soft music during breaks in the ward

kitchen. Attracted to the

sound, patients sometimes woke up and hung out, even sat around and had a few cocktails

of Coke mixed with ethyl alcohol.

Back in the

barracks, as an initiation rite, a newcomer’s first cocktail often came with

the hidden ingredient of analysis dye, causing their urine to glow hot

pink. Another common trick involved pouring raw ether on each other’s sleeping bodies, which felt and flowed like ice but also provided enough delay for a culprit to

get away before the victim jumped up and screamed.

His first morning after, hung-over and dying of thirst (only to drink some water and feel like he was drunk all over again), Ed woke up to the prodding of the same group of nurses he had spent the night partying hours before now full of pep and happily going about their morning routines as usual.

“Look,” Meneeley

said, “I feel like shit. How are you all

up bouncing around when you drank just as much?”

One finally admitted, “We always

take a fistful of B vitamins before going to sleep.”

7

Finishing

his night duty stint, Meneeley’s first daytime assignment made him responsible

for between 5-7 patients. While relieved

of the graveyard shift, his new role took on more direct responsibilities, including

having to control when his patients ate.

Because they had no control of their bowl movements, Meneeley was responsible

to remove the waste.

On his first round, a nurse instructed him how to insert a catheter, as well as how to lubricate a rubber-gloved hand to remove colon waste from a patient’s anus before it became toxic and poisoned their bodies. Before the conclusion of the first demonstration, Meneeley vomited.

On his first round, a nurse instructed him how to insert a catheter, as well as how to lubricate a rubber-gloved hand to remove colon waste from a patient’s anus before it became toxic and poisoned their bodies. Before the conclusion of the first demonstration, Meneeley vomited.

|

| Marlon Brando in The Men |

This was

his indoctrination. Reflecting on this

moment, Meneeley considered the role cultural conditions of his upbringing played

in his reaction. “It was all

bullshit!” Meneeley screamed, pounding his fist on the table, knocking my tape-recorder

to the floor. “This person was not going

to call you a shit-digger! He was

relying on you for an essential function of life support. The bonding, the intimacy of the situation

once you got past the surface details, it was…incredible.”

After overcoming

the repulsive reflex of his new assignment, Meneeley settled in helping to make

his patients as comfortable as possible to build back their strength.

One of his most

notable patients was Herbie Wolfe, a quadriplegic who served as gunner on a

destroyer commanded by Admiral and Film Director John Ford. According to Wolfe, Ford led the crew of his

ship like he led his film crews, taking a special interest in each crew member,

and often sent Herbie weekly stills from films he was working on, including My Darling Clementine. This attention piqued Wolfe's interest in the cinema, so Ed often wheeled him to

the hospital’s upholstered movie theater to watch the daily changing features.

Due to Riverside's proximity to

Due to Riverside's proximity to

When a

close friend of Admiral Ford, Fred Zimmerman, got set to direct The Men, he hired Herbie Wolfe as technical advisor in what

would become Marlon Brando’s first film.

Only 2 years younger than Brando, Ed watched the young actor learn how to spin a wheelchair around from some of the most

proficient, massive upper-bodied patients. Refelcting back on this time, Meneeley marveled at how his life was certainly turning

out a lot different than he previously had imagined back in Wilkes-Barre

“For two

years I had no communication with my father and step-mother. We worked hard,

cleaning, bathing, treating bedsores, lifting spirits," he recalls. "I became a totally changed person."

Such experiences away from home debunked most of Ed's ingrained cultural prejudices, landing him in a better position to go with the flow. This attitude would eventually give him access to many major players in the contemporary art world.

Such experiences away from home debunked most of Ed's ingrained cultural prejudices, landing him in a better position to go with the flow. This attitude would eventually give him access to many major players in the contemporary art world.

8

|

| Brando in The Men |

In some

cases, families of paraplegics became closer together, others got divorced. Meneeley described how so many young couples embarked upon a very new proposition. While the

men were still capable of having erections, they could not feel them or have

any control over when they might expire.

This forced the ladies to learn a different technique more akin to

artificial insemination than romance to produce children. And once a husband

and wife were forced to confront that adjustment, separation was often

imminent.

In that

sense, Meneeley watched the visitors as closely as his patients. This melancholic undercurrent in the ward allowed for all kinds of restricted activities in which most nurses and staff were aware but kept quiet from the

brass. One example centered around one young,

legless Marine paralyzed from his waist down and severely depressed upon his

arrival.

Meneeley described him as “extraordinarily charming and good-looking, so everybody

appeared taken with the demoralized boy.”

Nurses and

staff conspired in the galley to pool their money and take him to town, but

would later settle with the small victory in succeeding to lift him into a

wheelchair. There he began a series of small explorations around the ward, and soon the young Marine’s world expanded. Eventually he would travel

further, gently flirting with the staff in hopes of going into town, settling

down only with visitations from his mother who had relocated from Seattle

This young marine soon

became a symbol of hope and quickly became the ward’s success story.

While having alcoholic beverages on base was illegal under Navy law, no one on

the ward thought anything of it...until a surprise Saturday inspection when an

admiral noticed the beer and all hell went loose.

While the hospital

had a heavy medical side to it with an attitude akin to the television series

*MASH*, management was handled by officers who, for the most part, kept their

distance. It wasn’t uncommon for two

patients to lure an officer between their beds and use their massive

upper-bodies to swing up and pummel the trapped brass for continuously berating

the broken soldiers. “You want us to

wear proper uniforms! We don’t have any fucking legs!” they’d shout while they

wrestled.

Around this

time the base was getting a lot of attention. Newspapers reported a movie was about to begin filming. Social clubs provided their idea of aid. Movie stars started showing up to entertain

with ad lib performances, or just come and go from bedside to bedside

chit-chatting. Curiosity mixed with pride

on behalf of the upper ranks brought more and more higher-ups in to parade the halls. When the ward received

notification visiting Naval dignitaries were coming, the Head Officer decided

to take it upon herself to make sure her ship was up to shape.

“A case of beer…in a military hospital…what

is it doing here?" the crotchety woman screamed at the nearest nurse, "Which one of you scumbags has been drinking on the ward!”

A sickly

quiet pervaded until the young Marine wheeled himself up.

The terrified

young nurse turned, her mouth dropped open.

“His,” she said.

Meneeley recalled:

They

just took him away from us, psychologically court-marshalling him right there on

the spot. Humiliated, the patient went back to the bed that afternoon and never

got up again. We all found ourselves

having strange bouts of anger. Two

months later he was dead. Perhaps this incident best explains my very

particular attitude toward authority figures.

Sixty years

later, I arrived at Meneeley’s small apartment with a DVD copy of The Men. Ed claimed he had never seen it and I was

excited at the prospect of watching it together. Perhaps he would be seen as an extra, we wondered before settling in to watch. As the opening credits concluded, Ed began to weep and would continue, often hideously, the entire 85 minutes. The morning after his exorcism, I experienced

some of the most lucid moments of our sessions together.

9

Up until the last

patient left Riverside

After many

patients opened up the kits and “smeared around for a while,” Meneeley walked over

to help clean them up, relocating the small canvases and paints under their

beds.

When more inspections

came, Ed took the contraband kits and hid them in the galley, waiting until people

eventually began to forget before smuggling the art materials back to the barracks,

hording the materials after throwing away the boxes.

Lying on

his back, Meneeley painted figuratives, street scenes, and memories of the Susquehanna

River and Market Street

Bridge

Once he finally

received his discharge papers, Meneeley packed up the excess supplies and sent

them to friends in Wilkes-Barre

10

The Navy’s lease on the country club was winding down and patients trickled slowly back to civilian life.

As the

wards cleared out, less people meant fewer regulations. No air-conditioning meant naked sleeping

bodies, prompting someone on a regular basis to sneak in and fondle Ed while he

was asleep. Just before the point of

ejaculation, Ed woke up, but by the time he came into consciousness, the person

had vanished. The first few times Meneeley thought he was dreaming until one

night he pretended to be asleep and identified the culprit through his slitted

eyes.

“I wasn’t

offended by it because the arousal took over the influence of my senses,”

Meneeley recalled, “but it did have a strangeness to it. The next day, I followed

him out of the galley, introduced myself and asked if he wanted to have a few

beers or catch a movie. Startled, without

a word, he ran away.”

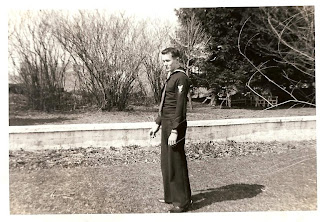

|

| Meneeley in WWII Navy Uniform |

“I didn’t

know what to do! Should I get up and scream?

Punch him? On a public

vehicle! Oh my god, I thought, this

is civilian life!”

Just a

couple of days left of out-processing and the upper-level mind-control specialists

took to lecturing Meneeley and his colleagues, praising them on their highly regarded

efforts, reminding them of their valuable service to the nation, filling them

with substantial doses of pride before attempting to hold on to as many of them

as possible as enlisted personnel in case of another national crisis.

“We were

told of plans to wipe out venereal diseases by testing at immigration. Officers

insisted it had nothing to do with politics, only medicine and national

health. The majority thought it a good

concept and agreed, but I wanted no part of that.”

Three days

before his release, Ed was woken in the night and hurried into the back

of a truck full of other sleepy-eyed servicemen. Minutes later, the truck lurched to a start and sped

away, canvas flapping in the wind. From

the higher elevations, Meneeley could see parts of LA in the distance, while a

prevailing sense of urgency provoked thoughts of a mysterious emergency. Radiation spill? Crashed UFO?

When dawn broke, he arrived at the base camp of a war zone, where fires burned in oil drums around a makeshift kitchen. Meneeley was offered soup and coffee before handed a rake and set to work making a fire break.

When dawn broke, he arrived at the base camp of a war zone, where fires burned in oil drums around a makeshift kitchen. Meneeley was offered soup and coffee before handed a rake and set to work making a fire break.

The next two

days passed in a mad dream.

Filthy

mules, BBQ, raking loose leaves and twigs, no sense of location or distance;

air thinned, depth perception skewed.

On the

third morning, he was released and decided on a slow bus ride home to Pennsylvania Las Vegas Texas

Back in Wilkes-Barre

Edward was headed home.

No comments:

Post a Comment